A United Approach in the Boreal Forest

We're conserving a vast forest of wildlife and carbon by partnering with Indigenous leaders and local communities.

Stretching across northern Canada from the Yukon to Newfoundland and Labrador, the country’s boreal forest is the largest intact forest remaining on Earth. This vast, interconnected landscape provides habitat for billions of birds every spring, gives room for moose and herds of woodland caribou to roam, and stores 208 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide—the equivalent of 26 years of global carbon emissions.

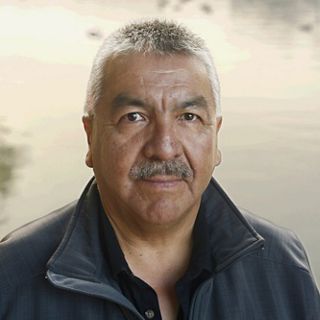

For thousands of years, First Nations communities thrived within the richness and sustenance of the boreal as the land’s original stewards. But as demand for resources grew, their authority over their traditional territories was challenged, their economies were destabilized and their immemorial way of living was threatened. Chief Clarence Easter leads the Chemawawin Cree Nation in Manitoba, Canada, which is partnering with Nature United: “We belong to the land; the land doesn’t belong to us. I’ve always lived off the land. Growing up, the land was your provider, your mentor, your healer; the berries you pick, the medicines you get, everything you got from the land … you didn’t rely on anyone else."

“In 1964, the Chemawawin people were relocated by the government to make way for a dam. We had no say. That’s what people don’t like, and they’ll resist it—all the way. They damaged our area with the flooding before; now they are going to desecrate it with cutting all the trees down. To me that’s not right. I’m not anti-development, but we need to maintain a healthy forest as well. How do we do that? That’s where we need some capacity.

“I need some science to be able to understand it, and be able to say yes or no—to government, to industry. That’s what I want to bring to the table. I’m hoping we can change some minds. That’s what I want from this agreement with Nature United, not just for our people, but for everybody else out there.

"We need to turn over a new leaf. The caribou, the moose, the ducks, the muskrat, the rabbits—they provided for us a long time before; now we have to do something to provide for them. I want to be able to come back in my next life to a clean environment that our grandchildren can live in, that will help them make a living. That’s what keeps me going; that’s the whole essence of why I am here."

Canada's Boreal Forest

Our Impact

Our work here started with a five-year partnership with Tolko Industries, a company that was responsible for a 22 million-acre forest tenure in northwestern Manitoba, the largest in North America. In collaboration with three Canadian environmental groups, Nature United embarked on technical research with Tolko to lay the groundwork for conservation, and for stewardship of woodland caribou, an indicator of healthy boreal forests. This work showed that it is possible to conserve millions of acres of wildlife habitat while supporting a sustainable forestry sector.

Our Approach

To achieve lasting conservation results, we are partnering with Indigenous communities and representatives from industry and government to create a future where healthy communities and responsible economic development drive locally and globally significant conservation outcomes.